Diaries of My Older Sister

By Terry Bu | 26 Sep, 2025

Terry Bu reflects on how societal pressures and negative self-talk contributed to the suicide of his brilliant and beautiful sister in her college dorm room.

My sister Katie committed suicide in her college dorm room a few

months before her 21st birthday.

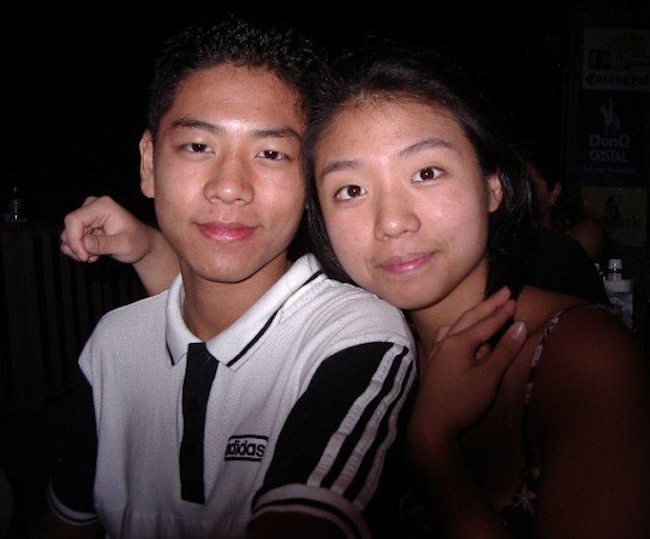

Terry Bu with his mother and sister Katie. (Terry Bu Photo)

When she was alive, Katie was deemed the model eldest Asian

daughter, the quintessential example of the “model minority.” She

was an overachieving straight-A student pursuing her double-major

STEM degree at a top university on full scholarship. Because of her

maturity, intelligence and caring personality, Katie was a great role

model for not just me but also for many friends who knew her. She

loved singing acapella, writing poetry, drawing and plant collecting.

Nobody could tell from looking at Katie that she had been secretly

suffering from crippling depression, bulimia and low self-esteem for

most of her young adult life.

Terry with his mother and sister Katie. (Terry Bu Photo)

Prior to her suicide, Katie had been seeing a campus psychiatrist

for several months after a romantic breakup. Her friends on campus

had been quite worried about her visibly changed, thin appearance

and mood changes. Her diaries indicate that she was forcing herself

on an extreme diet only eating one apple a day and then filling

herself up with water. On one particular afternoon, she received a C-

on her biochemistry midterm exam. Katie was the type of person

who could not stand anything less than perfection from herself and

always tried to meet the high expectations of being the model Asian

daughter. She might have been in a particularly vulnerable mental

state that day, with her relationship issues and eating disorders

compounded on top of this incident. According to Katie’s friend who

had talked to her earlier that afternoon, this exam score might have

felt devastating for her and pushed her over the edge.

A page from Katie's diary. (Terry Bu Photo)

By the time Katie’s roommate discovered her in her room with a

plastic bag over her head, she had been without oxygen for way too

long. I still clearly remember the night when my mother and I

received a call from the school hospital telling us that Katie had tried

to hang herself. Katie was taken to the ICU where she fell into a deep

coma and diagnosed with severe, irreversible brain damage. She

spent her last weeks in the hospital hooked up to a life support

machine while my mother, a few close family friends and I prayed for

a miracle. After months of no noticeable improvement, we were

forced to agree with the doctors to turn off her life support.

The rest of the world seemed to move on after Katie’s death, but it

wasn’t easy for my mother and me. After her death, her campus

psychiatrist sat us down and said, “Katie suffered from severe

depression due to her oversensitive personality. Medications did not

seem to help her. We are sorry.” I remember angrily thinking, “That’s

it? That’s the best explanation you could come up with?” I could not

believe that was the extent of their knowledge. My sister’s death

definitely deserved a better explanation than that.

Katie and I had been very close and were almost inseparable when

we were little, spending all of our childhood years together. Over the

last 15 years, as her younger brother who loved her deeply, I have

tried to unravel the truth behind why Katie might have been so

compelled to commit suicide. It just didn’t make any sense to me—a

person as intelligent as her deciding to throw away her own life at

such a young age. I studied the nature of depression and reviewed

Katie’s handwritten diaries that she had kept since she was 12 years

old. I analyzed her writings carefully, hoping to gain more insight

into the inner workings of her mind, thoughts and emotions while

she was alive.

Me and Katie growing up in South Korea and Japan

And what I started to realize, 15 years after her death, is that no

single person or event might have been to blame. I strongly believe

that Katie’s suicide was not just an isolated event based only on her

specific circumstances, but the result of a very noticeable general

pattern related to depression and suicide worldwide. This may be a

trend that has particularly impacted demographics such as South

Koreans, Asian-Americans and young adults in the U.S.

Research in psychology shows that there is a strong connection

between our mental narrative and depression. “Mental narrative” in

this context means the stories you tell yourself in your own mind and

the way you talk to yourself, commonly referred to as your internal

dialogue or self-talk. According to a study published in Social

Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience in 2016, “maladaptive

rumination” or the act of repetitively thinking negative and

distressing thoughts about one’s life is one of the most common tell-

tale causes of depression.1 Certain personality traits such as

perfectionism, neuroticism and excessive focus on relational status

(how you compare to others) all contribute to this harmful mental

habit and are most commonly found in chronic depressive patients.2

Katie had clearly expressed similar thought patterns in her own

diaries and in her interactions with others when she was alive. Katie

used to think of herself as fat, ugly, broken and stupid, when in fact,

she was talented, beautiful and intelligent.

Left: One of Katie’s last diary notebooks she kept until her death

Right: A page from her diary. In the right column, Katie lists out the reasons she dislikes

herself, “stupid, weak, fat, unlikable and not cute.” In the left column, she lists her positive

qualities such as having a loving family and good grades in school. It shows her final

attempts to remain positive despite her frequent, self-loathing rumination

살 아 가 는 내 가 되 어 야 지 .

다 는 오 지 않 을 이 0 중 한 하 루 를 알 자 게

괴 로 운 생 각 은 점 어 버 리 고 , 오 늘 하 루 만 큼 은

내 가 외 로 운 이 유 는 바 로 나 가 어 리 석 기 때 문 이 야 .

나 는 외 톨 이 가 아 니 다

어 디 에 나 , 어 디 서 나

나 를 아 껴 주 는 이 들 이 있 다

살 아 가 는 내 가 되 어 야 지

하 지 만 누 구 보 다 도 오 늘 의 이 한 등 간 을 보 람 있 게

내 일 보 다 여 유 있 게

어 제 보 다 너 그 럽 게

오 늘 은 좀 더 강 한 사 람 이 되 어 야 지

k a . 1 5 : 0 0

One of Katie’s diary entries in Korean. Translation: “I will try to be a little stronger person

today. I want to live every day and every moment the best I can. There are people who

value me, I am not alone; the reason I feel lonely is because I’m too stupid to realize that. I

need to stop thinking painful thoughts. I will live today as best as I can because today is

precious and will not come back.”

The insights I gathered from Katie’s diaries led me to ask if others

suffer from similar thought patterns. The answer was a resounding

yes. A 2009 research study published by the University of Maryland

School of Public Health found a pattern of strong mental stress

among Asian-American young adults in terms of “pressure to meet

parental expectations of high academic achievement”, “living up to

the model minority stereotype”, “difficulty of balancing two different

cultures and communicating with parents”, and “discrimination or

isolation due to racial or cultural background.”3 The Anxiety and

Depression Association of America also reports that Asian-

Americans are three times less likely than their non-Asian

counterparts to seek treatment for their mental health concerns

because “doing so would admit the existence of a mental health

disorder, and in turn would bring shame to their family’s name by

appearing weak or imperfect.”4

Traditional Asian cultures have long indoctrinated their people to

value academic performance, high social status and professional

advancement as top priorities in life. But our community has not

been successful in prioritizing the importance of mental health

awareness, emotional intelligence or helping younger generations

develop a strong sense of self-love or self-identity first. This might

have been the case with Katie as well. She never learned that caring

about her own mental health and changing the way she thought

about herself were just as important as getting good grades in school

or achieving “success” in the eyes of others. She silently pursued the

Asian vision of “success,” suffered quietly by herself like a mature

older Asian daughter and then died quietly in her dorm room.

We are also not the only South Korean or American family that

has directly or indirectly experienced the effects of depression and

suicide. It’s been reported that South Korea has the highest suicide

rate among the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development) member countries of the world. Many high-profile

South Korean celebrities, musicians and even a former president

have committed suicide over the recent years, citing reasons such as

shame, guilt, self-loathing and social pressure. In the United States,

suicide rates among teens and young adults regardless of race have

reached their highest point in nearly two decades with an annual

increase of 10% between 2014 to 2017 according to the U.S. News &

World Report in 2019.5 In addition, a 2018 report from the Blue

Cross Blue Shield Association also found that diagnoses of major

depression among its patient members swelled by 33% between 2013

to 2016 for all adults, 63% for teens and 47% for millennials.6 “We

are concerned that depression rates are continuing to accelerate, and

we need to do more work to identify the underlying cause,” says Dr.

Trent Haywood, MD, Former Vice President and Chief Medical

Officer for the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association.

I wrote this book to remind everyone that our understanding of

clinical depression as well as our cultural definition of “success” must

evolve to create a healthier and more balanced mental narrative for

people all over the world. The Asian-American and South Korean

communities in particular are great examples of the damage that can

stem from a distorted mental narrative on a societal scale. In a

culture that considers lagging behind your peers in academic,

professional or personal achievements a cause for great shame and

disappointment, there is bound to be mental turmoil among its

people, especially young adults who are emotionally sensitive and

susceptible to external influence.

The first section of this book covers the different types of harmful

mental habits that people vulnerable to depression are likely to

engage in and how they manifest in the form of automatic, repetitive

thoughts in your mind. These thoughts then may cause people to

suffer from a stressful mental activity called “rumination” which is

well-documented in psychology as a precursor to major depression.

The second section covers the possible origins behind how and why

our mind creates these stories. We will cover the impact of childhood

experiences, parental upbringing, cultural influences, social media,

peer pressure, neurochemistry and more. The last section discusses

the possible strategies we can employ to change our mindset going

forward as individuals and also collectively as a society.

I don’t claim to be a certified expert on mental illnesses. I

definitely do not have all the answers myself. I think of myself more

as a messenger of the already existing, complex knowledge out there

regarding these topics, and this book is my attempt at distilling that

body of knowledge and current findings for you so that the general

public can elevate their level of understanding. I do consider myself a

committed student and a first-hand observer of the nature of

depression because of how dramatically it has impacted me and my

family. But I also encourage you to think objectively about the ideas

in these pages, challenge them if necessary and verify the truth for

yourself. If this book can guide a few of you into having a better

understanding of depression and of how you can help yourself and

others, it will have achieved its purpose. I look forward to sharing

this story with you. We thank you wholeheartedly for reading our

book.

I: Observing Our Mind’s Stories

Causes of depression can be highly complex, difficult to pinpoint and

specific to the individual. Nevertheless, researchers have found a

strong link between depression and our mind’s automatic negative

thoughts, or the habitual stories we repeat to ourselves. The

academic term for this type of mental activity is “rumination.” Based

on my sister’s diaries as well as my own research and experience, the

following types of rumination may be commonly shared among

depressed individuals as well as those at risk for depression.

Observing our own mind for such types of thinking patterns may be

crucial for maintaining a healthy mind.

Chapter 1

“I am not good enough”

When you look at yourself in the mirror, what do you see? Do you

see somebody amazing in your eyes?

All my childhood, I looked up to my older sister like a JV

basketball player on the bench looking up to the captain of the

Varsity team. She was a straight-A student, spoke English, Japanese

and Korean perfectly by age 16 and had numerous talents like

singing, writing and drawing. In college, she double-majored in

Marine Biology and Environmental Science with ambitions of

studying Neuroscience. She won poetry competitions and was elected

president of multiple extracurricular clubs. Compared to her, I felt

like a stumbling little idiot throughout my childhood and relied on

her for anything even remotely difficult such as homework. One of

the reasons I started being a class clown and telling more jokes as a

kid was I felt it was the only way I could stand apart from Katie. My

parents and relatives all used to say that Katie was the smart,

responsible and mature one, and I was the rambunctious, awkward

little brother.

But Katie’s diaries tell a different story. For as long as she was

alive, Katie had been under the impression that she was not good

enough. Not pretty enough. Not thin enough. Not smart enough. Not

socially vibrant enough. Not talented enough. She wrote frequently

about how much she hated herself and all the negative qualities that

she saw in herself. In high school, she seemed to have beenparticularly hurt and distressed when her boyfriend at the time

would talk to other girls in her presence and immediately concluded,

“Oh, I must be a really boring person and he must be tired of me

already.” Katie was always very hard on herself, not giving herself

enough credit for her numerous qualities and achievements.

One of the most harmful mental habits is this tendency to talk

negatively about ourselves and to talk down to ourselves. This kind

of thinking is especially common in Asian families where parents

literally say “You are not good enough” to kids unless they get

straight As on their report cards. When this kind of self-critical

mindset bleeds into other parts of your life so that you constantly feel

inadequate about yourself, mental stress may not be far behind. This

mindset is also quite prevalent in people vulnerable to depression.

Because they carry this enormous burden thinking they are not

“good enough” at all times, they might resort to perfectionism or look

for ways to overcompensate for these imagined deficiencies. Or they

might even choose to resort to escapism or temporary pleasures to

disguise their painful feelings of inadequacy.

I pray that you do not let this particular mental demon lead you

astray. You were born “good enough” regardless of your intelligence,

looks, talents or achievements. We must not obsess over our

imperfections, especially because every single one of us is imperfect

in one way or another. The very belief that you are not “enough”

unless you meet certain qualifications in life is extremely flawed.

Others may judge you for this quality or that quality and try to tell

you that you do not meet some imaginary criteria that are important

in their own mind. In fact, your own mind can sometimes be yourown worst judge and constant, harsh critic. Oftentimes, you must

tune them out.

When we decide to see the beauty in ourselves despite our

imperfections, we will soon begin to see beauty everywhere—in our

lives and the world at large. Granted, this kind of mental perspective

is not easy to change overnight, but it’s important to keep reminding

yourself on a daily basis that you truly are good enough. You always

have been good enough. Any future effort to improve yourself then

doesn’t have to come from a place of “wanting to be good enough.”

Instead, it will come from your genuine curiosity and passion for

whatever action you decide to engage yourself in. If Katie were alive

today, I would try to remind her as often as possible about all the

beautiful qualities that she possessed, and perhaps help her stop

obsessing about all the imperfections she saw in herself. Her lovely

cooking skills. Her amazing voice. Her friendly personality. How

smart she was. Although it’s too late for me to say anything like that

to Katie, I now try to be more encouraging toward others and also

toward myself. I am good enough, you are good enough, and as long

as we are doing our best to become better everyday, that really is

good enough. And by being more liberal with our compliments

whenever we see other people trying their best, we may be able to

make the world a slightly less judgmental place, and fill it with more

acceptance and love.

One practical exercise I want to suggest is keeping a daily journal

of your biggest strengths and accomplishments. Go buy a notebook

and write down every morning (or every night) a short list of your

positive qualities and recent “wins” that made you feel good about

yourself. Any small wins will do; they don’t always have to be majorachievements like getting promoted or acing your midterm exam.

These can be private victories that still make you feel good no matter

how small. For example, the extra effort you made to cook dinner

last night even though you felt tired after work. Or an act of kindness

you showed to your work colleague who was struggling with a

project. Or the way you assertively stood up to somebody. Then as

time goes on, engaging your mind repeatedly in this “wins” journal

will serve as an oasis for your self-love and help build you up. By

reminding yourself daily about the victorious moments you’ve had in

the past when you felt the most joyous, happy, successful, intelligent

and proud, you are able to relive those feelings once again in the

present moment and feel like a winner again. Otherwise, in our busy

lives, it’s easy for us to lose sight of ourselves and encounter negative

influences or people in our environment who are quick to point out

whenever we mess up or make us feel like we are not “good enough.”

We must effectively build our own mental barriers inside our mind

against such influences, and this journal is a good example of that.

And once you can recall with absolute ease those past moments

where you flourished with your wonderful qualities, nobody can take

them away from you. They will be yours forever. Hold onto those

memories like precious gems, because that’s really what they are.

Rare gems for your soul.

Chapter 2

“I am ugly and unattractive

”

Katie used to believe she was ugly. Growing up, she particularly

hated her dark-skinned complexion, which both Katie and I

inherited from my mother’s side of the family. In traditional South

Korean culture, dark skin is not always considered an attractive

physical trait, and generally speaking, young women prefer having

white, porcelain-like skin. This leads them to spend an exorbitant

amount of money on skin care and makeup products that make them

look whiter. My mother, sister and I all used to share the same

inferiority complex about our skin color because so many Koreans

had made fun of us in the past. In Katie’s group of female Asian

friends, they would always try to look lighter and prettier like the

celebrities on TV. I don’t think Katie ever learned to love her skin

and appearance. In her diary entries before her death, she even

called herself a “dark, ugly duckling.”

In South Korea, there is a huge demand for plastic surgery—from

both men and women—which has made Seoul the world’s “plastic

surgery capital.” Business Insider reports that, at nearly 1 million

procedures a year, South Korea has the highest rate of cosmetic

surgery in the world, and 1 in 3 South Korean women between the

ages of 19 and 29 may have now had plastic surgery.7 Many people

decide to treat this simply as a “cultural phenomenon,” but I can’t

help but wonder if there’s any underlying problems in a culture

where young adults become obsessed with looking better and prettierthrough any means necessary. Plastic surgery may help young adults

resolve their appearance-based insecurities from the “outside-in”

instead of the much more difficult “inside-out.” Granted, the latter

approach is much harder and requires building up one’s self-

acceptance from the ground-up. It may even require constantly

reminding ourselves that smaller eyes, a smaller nose, or darker skin

color are all completely okay and not “ugly.” But I doubt that highly

lucrative plastic surgery clinics making their big bucks will remind

you to “strengthen your inner self-acceptance” in their poster ads.The three physical features described above, including double eyelids, prominent nose

bridge, and fair skin, are high in demand by young South Korean adultsIn a world where beauty standards are thrust upon us from all

angles via television, social media and advertising, it becomes almost

impossible to hold on to what makes you unique and to think of

yourself as beautiful. But what makes someone “beautiful” is often

changing, incredibly subjective and open to interpretation. I think

about Katie and all the young adults who might be self-conscious

about their physical appearance and cannot help but be angry at the

external influences that might have negatively impacted their self-

perception. As cliché as this sounds, the constant messages we

receive from advertising, television, Hollywood and social media

affect our perspectives significantly and often negatively. And today’s

media creators who produce videos, shows and movies can

sometimes be incredibly irresponsible with the messages they send

to young adults (who then soak them like sponges) since they are

incentivized to create shocking or visual content that easily grab

public attention, and not at all incentivized to think about the

psychological effects they may spread to their viewers.

If it were up to me, I would remind you that you are beautiful, no

matter what you look like. Every single person in the world is born

beautiful, just as you are. God would tell you the same thing. Please

don’t let anybody tell you any different. At the risk of sounding like

an old grandpa, your external appearance is not nearly as important

as the inner beauty that you cultivate inside your mind, such as your

values, wisdom, passion and compassion for others. External beauty

also fades with time while inner beauty does not. Granted, there are

things that we can realistically do to improve our external

appearance such as keeping a healthy diet, exercising, taking care of

our skin and dressing better but at a certain point, we must limit howmuch focus we give to our appearances. If you are concerned that

others won’t take notice of you because you are not physically

attractive enough, I want you to know that the right people will take

notice of you for the right reasons regardless of your physical beauty.

Chapter 3

“I am behind compared to others

”Competitiveness is ingrained in all of us. As a kid, I would become

upset with my friends whenever they beat me at games like poker or

basketball. Now that I’m older, I look at a friend who owns her house

and think “Wow, so impressive. I’m so behind than her.” I look at

someone who’s been promoted to VP at a major corporation and

think “Wow, VP at 30. I’m so behind.”

Comparison is this endless losing game. Anybody can find

somebody else who’s better at something than they are. I may be

better than my friend at playing the guitar but he may be better than

me at running marathons. So does that mean only one of us is

deserving of love and respect? Surely, that’s ridiculous. But this kind

of “comparison-based thinking” happens all the time, and we suffer a

great deal from this mindset unless we learn to control it. Obsessing

about your own status in comparison to others and “where you

stand” in relation to others can be a common trigger for stressful

rumination and harmful overthinking. What’s even worse is that

when people around you are being competitive, their competitive

thoughts and feelings can trigger your own competitive nature.

Katie seemed to play this comparison game a lot when she was

growing up. She would get visibly upset if I performed better than

her at certain activities like playing golf or computer programming.

It made me want to yell at her, “Katie, you are better than me in so

many other ways. You have so many other talents like drawing and

singing. Why are you so upset that I am better at these few other

frivolous things?” Her diaries show that she engaged in the same

comparison-based thinking when it came to her peers in high school

and college. “Oh, she is more interesting than me. I’m nothing like

that,” or “Oh, he went to a better school than me. I’m nothingcompared to that.” All that comparison thinking seemed to get her

down a lot.

I’ve known many South Korean and Asian-American peers who

strongly exhibit this comparison mentality. Asian parents seem to be

literally born with the disease of comparing their children to other

children as if all that comparing is going to actually help the kids

achieve more or become mentally stronger. South Koreans actually

have a term for this called “엄친아” (pronounced Um-Chin-Ah which

translates literally to “your mother’s friend’s son”) when your mom

constantly compares you to her friend’s son or daughter who’s doing

a lot better than you in life. For example, “Hey son, did you hear

Jane’s son is now making lots of money as a doctor, living in a luxury

apartment and traveling all the time? She must be so proud of him.

When are you going to be more like him?” is something you might

typically hear during a dinner conversation. If you have parents like

that, you should try your best not to take their comments too

seriously. When I was a kid, I would listen to these comments so

seriously and internalize all of them, which then filled me up with a

mix of competitive anger and disappointment in my own status.

Nowadays, I interrupt her and say, “Mom. I have my life. He has his.”

Many Asian parents erroneously believe this kind of comparison

can be used as motivation to push their children further. Although I

do not blame parents for wanting the best for their children, they are

incredibly unaware of the anger and self-hatred they can impart to

their children if this kind of comparison-mentality becomes

excessively frequent. The competitive nature that exists in all of us is

fueled even more by our parents who are basically pouring gasoline

on a wildfire. Granted, we have to appreciate the fact that most of thetime, our parents are just trying to nudge us toward the right

direction with no knowledge of any potential harm. However, even

they don’t realize that unhelpful mental narratives may then trickle

down into the children’s psyche who may end up compensating by

constantly trying to prove they are better than others or obsess over

falling behind. As hard as it may be for our parents to admit, we must

sometimes block out their influence for the sake of our own mental

health.

We can learn to harness our competitive nature instead of letting

it drive us crazy or obsess about how we compare to others. I am not

encouraging that you don’t push yourself to perform at your best or

stop caring about competition altogether. But notice how easy it is

for us to get fixated on “beating others.” Being overly competitive

tends to make us lose sight of what’s truly important. For example, if

you are playing a basketball game with your friends, is it more

important to hog the ball and prove yourself as the best player in

your group, or to enjoy a great time with everyone and share the ball

instead of keeping score? If you are constantly being competitive

with a particular coworker, is your competitiveness contributing to

the company as a whole, or is it needlessly stressing everyone out? If

you obsess over beating your friend’s exam score in class, are you

actually paying attention to the material that you should be learning?

Comparing yourself to others may only serves a useful purpose if

you can then apply that information for a useful purpose. Perhaps to

gauge how far you’ve come in some aspect of your life. Professional

athletes often use competition to motivate themselves to perform

better and to learn from their rivals. However, you must not let it

consume you. Choose to free yourself from the game of constantcomparison. Watch out when others try to pull you into a

competitive mode by trying to one-up you or showing you how they

are better than you every chance they get. Spend your thoughts and

energy on becoming the best you that you can be. Use that

competitive drive for you instead of against you by daring to be

better than you were yesterday and committing to improving

yourself daily. People who are capable of great focus and mastering

difficult skills are proficient at being in the “zone” or the “flow state”

where their brain is 100% immersed in whatever task they are

mastering at the time, instead of being distracted by competitors,

haters or naysayers. It’s almost ironic but in order to compete, you

must master your craft, but in order to master your craft, you must

effectively block out all distractions (like your competitors) from

your mind.

Lao Tzu, the ancient Chinese philosopher, has a famous proverb

that says “大器晩成” (pronounced “dà qì wǎn chéng” in Mandarin)

which directly translates to “A large vessel takes a long time to

make.” Another translation is “Great talents take a long time to

bloom.” When you feel that you are behind in life, remember this

proverb. Remember that you are a late bloomer. And when you

finally do bloom later in your life—and this will absolutely happen as

long as you stay persistent and determined—you will bloom brighter

than any other flower the world has ever seen before. Do not wish for

an easy life or an early bloom. Your best is yet to come.

Terry Bu with his sister Katie. (Terry Bu Photo)

Asian American Success Stories

- The 130 Most Inspiring Asian Americans of All Time

- 12 Most Brilliant Asian Americans

- Greatest Asian American War Heroes

- Asian American Digital Pioneers

- New Asian American Imagemakers

- Asian American Innovators

- The 20 Most Inspiring Asian Sports Stars

- 5 Most Daring Asian Americans

- Surprising Superstars

- TV’s Hottest Asians

- 100 Greatest Asian American Entrepreneurs

- Asian American Wonder Women

- Greatest Asian American Rags-to-Riches Stories

- Notable Asian American Professionals